ls stands for list

List out the contents of a directory. If you don’t specify anything else, ls will list the contents of the current directory. That’s the same thing as

ls .

Remember, the period (.) refers to the current working directory. So this is like saying, “List the files in my current directory.”

If you tell ls to list a different directory, like a subdirectory:

ls abc/

This will list the contents of a directory inside the current one. If there is no such directory, it will tell you like so:

ls: abc/: No such file or directory

Remember, the other rules of file paths apply here too, so ls ../ (parent directory), ls /usr (the /usr folder at the root of the hard drive), and ls ~/ (the current user’s home directory) all work too.

ls takes a parameter that is a UNIX path matcher. You already know what a UNIX path matcher is because you’ve used it, probably. You’ve learned the rules of home directory (~), current directory (.), parent directory (..), and root of hard drive (/), but what makes a path matcher different from specifying a full file name is that when you use a path matcher, you’re saying “any file that matches this specified part.” For example, if you specify ls a_directory, where you have a directory called a_directory. The list command will list all of the files that are in that directory because all of those relative paths match what you specified.

Using a Wildcard in A Unix Path Matcher

But you can make it more interesting but using a wildcard.

These path matcher rules apply to all UNIX commands, not just list. Any time you need to pass a reference to a file or set of files, you can probably pass a path matcher. (If you can’t, the documentation may tell you you must use a “full path” or “specific path”.)

Using a Flag with A Unix Command

Passing a flag means we type the command followed by some special characters that tell the command to work in a specific, non-standard way. Most flags have a long form, which is denoted with two dashes (–) and a longer word and a short form, which is denoted with one dash and a single character.

Sometimes, you’ll want to combine flags. That means you run more than one. When you use the short form (a single dash), you can combine multiple flags after the dash, without using a dash for each letter

.

Let’s take a look at our first flag.

The -A Flag (Show All Files, including Hidden Files)

The -A flag shows all files, including hidden files. (The ones that normally begin with a period.)

The -L Flag (Long Format)

The -L flag shows the long format. When viewed in a long format, each file entry gets its own line. You also see more information: The owner, group, and file permissions. We’ll return to the concept of the owner, group, and permissions later in this course.

For now, just remember that the -L format shows you all of this information, and this command with the -L flag is a great way to examine your file permissions.

What if you want to look at both long format and invisible files? You combine the flags by simply combining each shortcode. In this format, you write only one single slash, followed by the l and the a

ls -LA

The -F Flag (Show Path Objects with Symbols)

The manual page for the -F flag says: “Display a slash (‘/’) immediately after each pathname that is a directory, an asterisk (‘*’) after each that is executable, an at sign (‘@’) after each symbolic link, an equals sign (‘=’) after each socket, a percent sign (‘%’) after each whiteout, and a vertical bar (‘|’) after each that is a FIFO.”

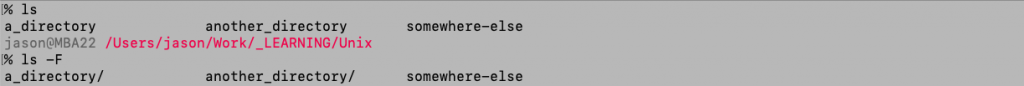

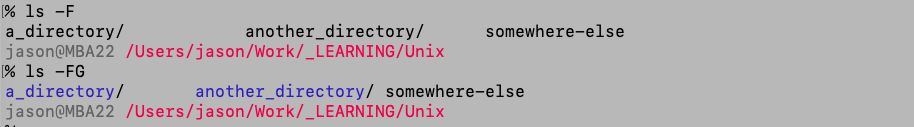

Notice how the directories don’t have trailing slashes (/) when you use ls with no flags. Directories have trailing slashes when you run ls with the -F flag.

The -G Flag (Colorized Output)

ls -G

Or combine it with the -F flag, as shown here:

Change Directory (cd)

cd stands for change directory. After you type cd, you give this command (and nearly all Unix commands) an argument. You do this by typing cd , and then a space, and then the argument at the terminal prompt

When you change the directory, you are changing the current working directory of the shell prompt itself to the new directory you specify. That means you “move” to the new location specified.

The first argument to cd is a relative folder location. (Remember, you can only specify folders or directories here— not files.)

Remember, as we covered in the last lesson, you begin your relative path in one of four ways:

- Using

.., which we learned about in the previous lesson, tells the prompt to go up one directory or to the parent directory. You can move up two directories using../.., or three directories using../../.., etc. - Using the name of a directory within the current directory, we can go down one directory into the directory specified.

- Using the home directory specifier (

~), we can go to the home directory or another directory relative to the home directory. (We learned in the last lesson that~means the home directory.) - Using the forward-slash (

/) at the start of the filepath indicates the hard drive root itself. You can then also use this to specify a full path (meaning, the path relative to the root), like/abc/xyz.

When you cd, you are changing the directory of your current working directory for the shell prompt you are currently using. Your next command will be interpreted from your new working directory. The new one might be relative to the CWD (as in the case with a relative path like . or ..) or it might be non-relative (as in the case of ~ and /). Either way, your current working directory will be changed. That’s this command is called change directory or cd for short.

Do not confuse this forward slash that comes as the very first character with other forward slashes that might come, for example, after a dot (.), two dots (..), or tilde (~). Those file forward slashes do not indicate the root of the hard drive.

Let’s move around our hard drive now using the following seven exercises.

Exercise 1: Move To Your Home Directory

cd ~

Type cd followed by ~ and hit return.

Exercise 2: Move the Root of Your Hard Drive

cd /

Type cd followed by a single forward slash (/) and hit return. (*Do not confuse the forward slash / with the backslash \)

Exercise 3: Move Back To Your Home Directory

cd ~

Same as exercise 1. You are now back in your home directory.

Exercise 4: Move Up One Directory

cd ..

Type cd followed by a space and then two dots (periods). Period characters are called “dots” in the context of programming. Hit return.

Notice that in macOS, you are now in the /Users directory. For WSL (Ubuntu) and most Unix systems, your user directories will be in /home instead.

Exercise 5: Move Down One Directory (back into your home directory)

cd yourname

(Instead of yourname you will type the name of your home directory.)

Exercise 6: Move Down One Directory (into any folder of your choosing in your home directory)

Pick any folder that you know is in your home folder. For example, I’m going to choose Pictures (it comes default with macOS, but this folder might not be present on non-Mac systems.)

cd Pictures/

I have now changed directory into the Pictures/ directory.

Exercise 7: Move Up Two Directories

cd ../..

Notice that we are back at /Users (or /home), where we were when we ran the command in Exercise 4.

When you have a solid understanding of how to move up a directory, move down a directory, to the root of the drive, and to your home folder, move on to the next lesson.

Let’s revisit something we learned in Lesson 4: Bash and Zshell

If your system is using Bash, you’ll have these files at the location of your home folder.

.bash_profile

.bash_login

.bashrcIf you have ZShell, you’ll instead have these files:

.zprofile

.zsh_history

.zsh_sessions

.zshrcFirst, change directory to your home directory with

cd ~

Now, let’s examine the home directory itself for files beginning with with either .bash or .zsh